Under The Tongue

Curated by Marie Catalano

January 14, 2016

7pm

Mary Wigman

Heidi Lau

Amy Catalano

Adam Putnam

Bonnie Lucas

“...I must draw your attention to the fact that when witches receive communion, they … receive the Lord’s body under the tongue instead of on top of it ... because this way it is easier for them to take the Lord’s body out of their mouth, as I have said, to make use of it in ways which will give greater offence [sic] to the Creator.”

-Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum, a treatise authored by clergymen and published in 1487 in Speyer, Germany, outlines a process for broadly identifying witches and advocates death and torture as punishment. Following the document's publication, Europe became hypervigilant of deviant behavior, particularly in women, who were thought to be more susceptible to demonic possession than men. The persecution of suspected witches rose in brutality leading to mass executions, which peaked in the 1500s and 1600s.

German dancer Mary Wigman choreographed her “Witch Dance” three centuries later. Today, you can watch fragmented footage of “Witch Dance II,” her second version, on YouTube. I’ve watched these clips repeatedly, fascinated by the terrifying momentum of her body. In her initial movements she appears to be in control and then the percussion mounts and it’s like something else is pushing her, like there’s something else in the room.

The works in this exhibition all reflect the presence of something else in the room, of something unexpectedly channeled in the process of their formation. Over the course of producing these objects and documents the artists have taken on a role similar to that of a medium, allowing for something outside of their immediate consciousness to be activated. Like Mary Wigman’s frenzied witch, they have let something seep in, leak out, or disperse altogether.

Mary Wigman (1886 - 1973)

Mary Wigman began dancing in 1913 at the age of 27 when ballet was the leading form of dance in Europe. Against the advice of a teacher and despite having what she called a “bony” and “not dainty” figure she attended dance school first in Hellerau, Germany and then became the student of modern dancer Rodolfe Laban in Switzerland. She choreographed the first version of her “Witch Dance” without musical accompaniment and performed it as her dance debut the following year in Munich. Her costume was composed of a shawl that she described as creature-like. Thirteen years later she choreographed a revised version of the dance, which included percussive accompaniment and a masked costume. The surviving video clips are from a 1930s promotional video for a tour of her performances in the US.

Wigman describes her early practice as a search for a way of dancing that had no precedent. Her objective during this time was to reach an ecstatic state, to dissolve herself into the physical elements of a room: “Time and again I gave myself up to the intoxication of this experience, to this almost lustful destruction of the physical being, a process in which, for seconds, I almost felt a oneness with the cosmos.”

Heidi Lau (b. 1987)

Lau grew up in Macau in the late 1980s and early 1990s while the city was undergoing a major political upheaval. Claimed by the Portuguese Empire in 1550, Macau became a Portuguese colony in 1887. In 1999, sovereignty of the state was transferred to China. Lau was 12 at the time, and recalls seeing this transition reflected city’s crumbling architecture. During this transitional period, many of the colonial municipal and residential buildings were left to decay, and once sovereignty was fully transferred to China they were gentrified beyond recognition or destroyed altogether. “The hometown I think about often was a very 'porous' city, with visible layers of time, history, and problems. ” says Lau. “For me, ruins are remainders and reminders for the future.”

Lau’s glazed ceramic works titled “Dark Castle” and “Cathedral” are turreted, biomorphic structures composed of fingerlike scaffolding. Small and intricately constructed, the works have an inherent devotional quality reminiscent of shrines. Lau attributes this in part to the prevalence of shrines in Macau’s urban environment which reflect the Taoist practice of honoring one’s ancestors as a part of daily life. At once skeletal and organic, the ceramics are dreamlike incarnations of the structures that the artist witnessed dissolving into and being consumed by the urban landscape.

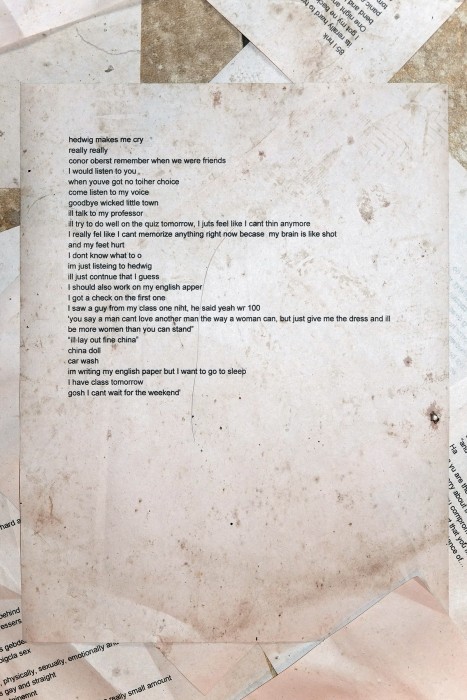

Amy Catalano (b. 1997)

Amy Catalano has been chronicling events that occur in her daily life in the form of handwritten diaries since the 5th grade. She is also my sister and when we were growing up I would drop off paged through copies of my fashion magazines to her room so she could use them for collages in the margins of her notebooks. When Catalano was 15, she began keeping a second daily writing log, which she calls her “Digital Diary.” Atypical of a traditional diary format, the document eschews narrative and is written in nonlinear sentence fragments, which often take the form of a list. The text is an impulsive collage of thoughts that suddenly give way to song lyrics, quotes from books, musings on banal daily experiences, moments of critical self reflection, and questions to no one: “Do you ever feel like the whole room is breathing and staring at you / like every part of the room was alive. [sic]” There is no editing process, either of the thoughts that come before she writes or of the text after the moment of recording transpires. According to Catalano, her “Digital Diary” came out of the need for a faster way of purging her thoughts so she could create more headspace for focusing on daily tasks. The pace of typing mirrored the pace of her thoughts more than writing by hand. Installed in the gallery, the document is scattered to cover the floor.

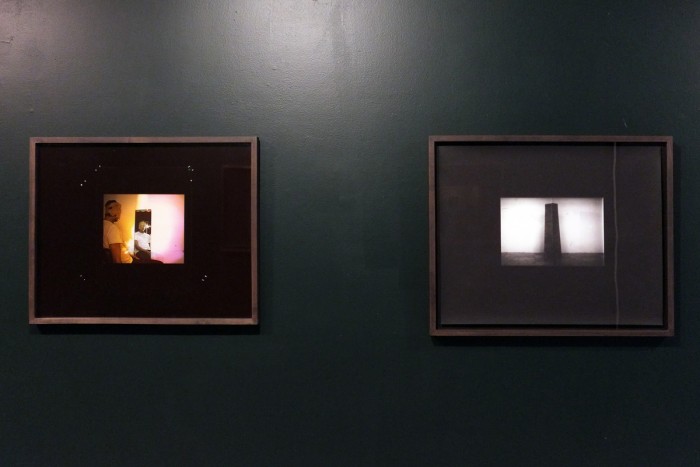

Adam Putnam (b. 1973)

Putnam’s work employs a range of media including performance, sculpture, video, and photography to investigate intersections between stillness, thresholds, portraiture and architectural space.

In “untitled (colonial threshold),” 2009 a wallpapered room’s lower half is shrouded in shadow. A doorway in the center is impossibly blacked out, like it could suction you up into the space of the room and beyond, into a total void.

Originally pulled from video stills, these photographs on view mark the beginning of what would later become a series of short video works titled Reclaimed Empire (Deep Edit) 2008-2015. Taking cues from older printing processes, the photographs were painstakingly contact printed using 4 separation negatives. Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black were exposed sequentially, culminating in a full color image. Traces of this archaic process can be seen in strange artifacts surrounding the image. “The original title, reclaimed empire, initially an overt nod to Warhol’s Empire, speaks less about homage, and more to the notion of a constant return to repeated subject matter - a gaze that never leaves, that stares un-blinkingly – mechanically - at the same subject,” says Putnam. “This was my Empire, comprised of whatever was on hand in my studio, sculptural fragments, broken mirrors, architectural models and other detritus.”

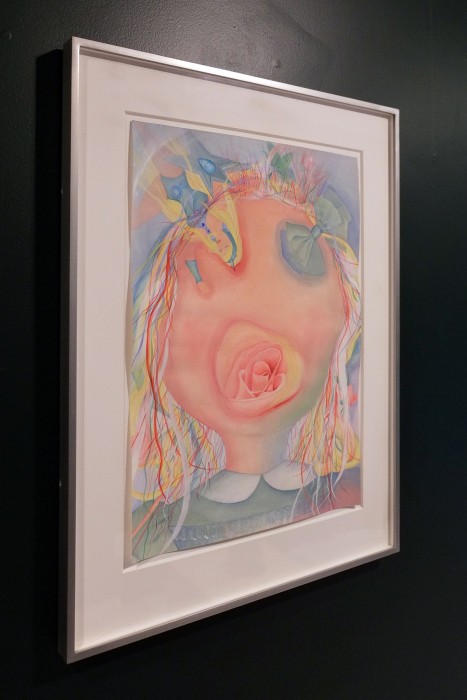

Bonnie Lucas (b. 1950)

During a summer break from Wellesley College in the late 1960s, Lucas took a job as the arts and crafts counselor at a girls camp in Maine and found she loved making art as well as teaching it. When she returned to college in the fall she began collecting eggshells from the school cafeteria to use in tiny assemblage works which she mounted on felt and gave away to friends. She graduated in 1972, when Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes had just published their first issue of Ms. Magazine. The cover illustration was of a pregnant woman with eight arms holding a different object in each hand: an iron, a frying pan, a typewriter, etc. The image left a strong impression on Lucas. “When I saw that, I panicked. I knew I didn’t want to do that...that juggling things and multitasking was absolutely not for me. I knew I wanted to pick a few things and concentrate on them and try to do them well, and that’s what I did.”

Lucas later received an MFA from Rutgers University and moved to New York to continue her studio practice. She taught at Parsons in the 1980s and early 1990s and is currently an adjunct professor at City College CUNY.

“And This Too Will Pass,” 1983 is one of the first works that Lucas made to depict a figure. In this piece, gloves, plastic spoons, a handkerchief and other common household objects make up a skirted, scarecrow-like figure whose head and limbs are all wildly out of proportion. Tiny strands of white thread outline the figure and create radiating lines that evoke rays of light. For Lucas, the shift to figuration was revelatory. “I felt that the figure had a sort of spirituality; that it was giving a benediction. Like some sort of idol that you would pray to.”

-- Marie Catalano